SAMS news room

Taking a microscopic look at our seas

Scientists have completed the first ever assessment of how plankton communities are changing in coastal waters and shelf seas around the UK.

Using an 11-year time-series of data, the findings create a snapshot of how plankton communities have changed and shows that the patterns of change differ spatially in UK waters.

Writing in the Ecological Indicators journal, researchers say the study offers an important preliminary insight into the status of the plankton, which play a pivotal role in the health of our seas.

A co-author on the paper is phytoplankton expert Professor Paul Tett of the Scottish Association for Marine Science (SAMS). He set up one of the oldest sampling sites in the UK, known as the Lorn Pelagic Observatory, more nearly 50 years ago and it is now one of 13 fixed sites around the country.

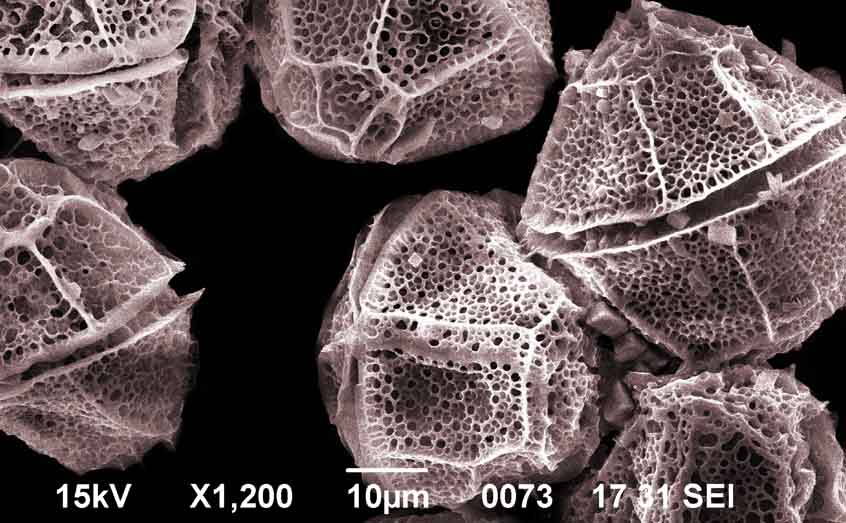

Prof Tett said: “Knowing the abundance of phytoplankton and the types of species in our waters is crucial for understanding what is happening in our marine ecosystems. Phytoplankton are the grass and trees of the sea – everything else depends on these microscopic organisms.

“Our central station was first sampled on January 6, 1970 and since then we have been observing the types of phytoplankton there and the abundance of each species. It is a bit like monitoring how much woodland is in a particular area, which species of trees and smaller plants are there, and the seasons in which they come into leaf and flower. One of the reasons we need frequent monitoring is because, unlike trees, phytoplankton are moved by water currents and can increase or decrease in numbers within days.”

The central station of the Lorn Pelagic Observatory is off the Greag Isles, near to SAMS. The observatory also includes sampling stations in lochs Creran, Etive and Spelve, where conditions have been studied by several generations of research students. In response to the growing number of data sets Prof Tett and his colleagues had amassed, he created software that shows changes in the balance of species in the phytoplankton. This method has been adopted nationwide, giving this new study a direct comparison between local sites.

The study was conducted by a network of world-leading scientific institutions and government bodies, led by the University of Plymouth, and also including: SAMS, Plymouth Marine Laboratory; National Museum of Natural History, France; Environment Agency; Marine Scotland Science; National Oceanography Centre; Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science; The Marine Biological Association; Agri-Food & Biosciences Institute; Trinity College Dublin.

Lead author Dr Abigail McQuatters-Gollop, Lecturer in Marine Conservation at the University of Plymouth and a Knowledge Exchange Fellow funded by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC), said: “For the first time ever we have a method to investigate how plankton are changing throughout UK waters.

“Without plankton we won’t have oxygen to breathe, fish to eat, or larger marine mammals to admire. Their health is important to the entire marine ecosystem and this research is a critical step in evaluating the environmental status of the pelagic habitat.”

In the UK and the Northeast Atlantic region, changes to plankton functional groups – or ‘lifeforms’ – is the formally accepted policy indicator used to assess Good Environmental Status (GES) for pelagic habitats under the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD).

Initially adopted by the European Union in June 2008, the legislation was updated in 2017 to give clearer guidelines as to what countries should do in order to achieve GES for European waters by 2020. Adopted into UK law, the policy of seeking GES will continue independent of Brexit.

This study forms the foundation of the UK’s 2020 MSFD assessment for pelagic habitat biodiversity and food webs. It was supported by funding from Defra, NERC and the devolved administrations in Scotland and Northern Ireland, and builds on Defra’s Lifeform and State Space project, which was led by the Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute in Northern Ireland and completed in 2015.

The full study – Plankton lifeforms as a biodiversity indicator for regional-scale assessment of pelagic habitats for policy by McQuatters-Gollop et al – is published in Ecological Indicators, DOI: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2019.02.010.